Funeral Falldown

So here is a quick case for the sake of looking at a new paper in context.

Mrs B is a 65 year old woman who has been brought in by ambulance from the local funeral home… no she is not dead. She was just at the home to view the cremation of her sister who did sadly pass away 2 days prior.

Mrs B. was attending the viewing with a dozen close family members when she was noted to fall down. She “became all pale”, “slumped to the floor” and groaned according to her daughter who has accompanied her in the ambulance. She thinks that she was unconscious for about 30 seconds before coming around and being a little disorientated. When the Ambos arrived she was GCS 15, normotensive and had a pulse rate of 80. A BSL at the scene was 6.5 mmol [117 for Americans]. She didn’t appear to have any injuries and was able to walk out to the ambulance. Her daughter did not see any convulsive / epileptiform movements.

Mrs B. is usually pretty fit and active with lone AF which has had a thorough work up a year prior including a normal ECHO and

She takes aspirin 100 mg/day and atenolol 50 mg/day

On initial assessment Mrs B. has the following Obs:

HR 85/ min in AF, BP 135/70, RR 14, SpO2 =97% RA, warm peripheries and GCS 15/15.

Clinical exam is unremarkable aside from the AF and she has no postural BP drop. There is no murmur and a quick neurological exam is plum normal.

She has a VBG and troponin sent – both of which are entirely normal. She has no anaemia or electrolyte anomaly.

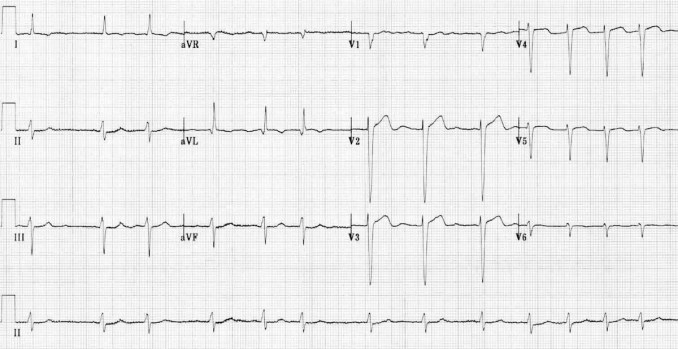

Her ECG is as follows:

Mrs B. feels fine. She has no symptoms when you see h

So. How to proceed. Should we send Mrs B. home? Should she stay and be monitored for awhile? OR is that just hedging the bets and sitting on the fence? Maybe she needs admission for a full work up…. what to do?

So before we move onto the science part – have a think about what you would do in your hospital or clinic with a woman like

Recently this paper was

Duration of Electrocardiographic Monitoring of Emergency Department Patients with Syncope by Thiruganasambandamoorthy et al

This was an observational study from the fantastic Canadians in Ontario. They included 5,719 adult patients presenting to ED within 24 hours of a syncopal event. They excluded patients with

- prolonged loss of consciousness (> 5 minutes),

- mental status changes from baseline,

- obvious witnessed seizure based on previous history or current clinical evaluation,

- head trauma causing loss of consciousness.

- accurate history was not possible (e.g., language barrier, intoxication due to alcohol or drugs).

The patients were risk stratified using the Canadian Syncope Risk Score (CSRS) which is available in MDcalc here.

For the exercise of this case lets us apply the CSRS to

The patients in the trial were then monitored in the ED for a period of time and then selectively either admitted or discharged and their outcomes followed up for badness (death, arrhythmia, MI, serious structural heart disease, aortic dissection, pulmonary embolism, severe pulmonary hypertension, significant haemorrhage, subarachnoid haemorrhage, any other serious condition causing syncope or procedural interventions for treatment of syncope ) for 30 days.

Interestingly, of the patients in the

Nearly 3/4 of the patients were classified as “low risk” [CSRS = to 0 or less], and this seemed to predict a better prognosis with only 15 (0.4%) having a serious dysrhythmia – mainly supra-ventricular dysrhythmias and heart block. About half were identified within 2 hours of ED monitoring. Importantly NONE of the patients in this low-risk cohort died or had sinister outcomes within 30 days.

In the medium-risk cohort [i.e. CSRS 1 – 3] 92 patients (8.7%) had serious arrhythmias about half of which were diagnosed within 6 hours of ED arrival on a monitor.

Lastly, in the high risk group (CSRS > 3) about a quarter went on to have serious arrhythmias diagnosed / bad outcomes. Once again approximately half were identified after 6 hours of ED monitoring.

Of the patients in the medium or high risk groups – about half got diagnosed on the 6 hour ED monitor. The other half were identified within 15 days of follow up monitoring.

So, back to the case… Mrs B. is very keen to leave and rejoin her family at the wake. She has been in the ED on the cardiac monitor now for 2 hours and you have had the chance to review her again and check all the investigations. She has not had any arrhythmia other than her chronic AF.

After an informed discussion about her risk you can tell her that she is very unlikely (ie. around 1%) to have a serious event in the next 30 days. The fact that she has had a benign, 2-hr period of monitoring roughly halves that risk again according to this new data. Of course, as a good GP, you can level with her and assure her that the most likely cause of her syncope was vasovagal syncope as a result of the intense emotional situation at the funeral home. This is completely ‘normal’ and is unlikely to recur in the future.

Mrs B. agrees to follow up with her family doctor and have ongoing BP monitoring and to take it easy over the coming days where she is likely to experience more stress and sadness. Her daughter is greatly relieved.

This data is observational. For a prognostic trial, this is a very large data set and the follow up within the trial seemed to be rigorous and as complete as one might hope in such a large population. 97% made it into the final analysis. The population was largely middle-aged Canadians. They seemed quite representative of a First World cohort with a typical spread of comorbidities.

I think that this data tells us that we can safely risk stratify syncopal patients using the CSRS into “low” and “not low” groups. Low risk patients who have been monitored in ED for a few hours are probably well below the threshold for any sensible further investigation.

Higher risk patients can be selectively admitted or referred for urgent investigations. It is important to recognise that the vast majority of arrhythmic events occurred in the first few days after initial syncope. This might change the way I go about organising follow-up for diagnostic Holter monitoring or Cardiology referral. Table 4 from the paper is below – this illustrates my reasoning for this practice change:

So – have a read of this article (full text linked above) and let me know – will it change your approach to syncopal patients? Casey

thank you, Casey. very cool blog. shall certainly be using the CSRS moving forward.

tom fiero

er doc, merced, ca.

I am a little bit shocked! However, this is being used in a general practice and yes, this data is observational.

Hi Casy.I am surprised she isnt on a NOAC if she has been in AF for a while