Clinical Case 057: big PE, now what?

This is a pulmonary embolism case – but I promise – not another diagnostic case. That territory has been well covered by all the big names in blogging over the past 12 months.

This case is about decision-making after the diagnosis is made. Risk stratification and the evidence as it stands in 2012…

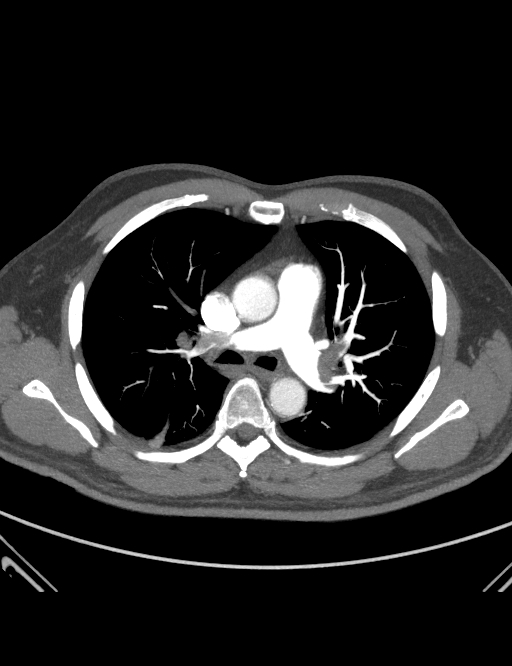

60 year old man, recently retired and on holidays in sunny Broome. Usually fit and healthy. Presented with chest pain, had a typical S, Q3, T3 pattern on the ECG, hypoxia on oxygen and a positive D-Dimer. He remained normotensive throughout, with a tachycardia of 110 in SR. So he got a CTPA… (there are 3 slices to see if you click the arrows)

OK, so the diagnosis is easy – he has PE (s). But now what?

Do we simply commence anticoagulation admit him and hope he doesn’t get really sick? Or should we look a little further and consider more aggressive therapy such as thrombolysis, or even referral for embolectomy?

These are tough questions – an not some we have to ponder often as most of the PEs we see are smaller, and don’t cause much in the way of cardiac dysfunction.

So how do we decide when we should be going for a more aggressive option – and what should we tell the patient in this scenario?

There has been a lot of research coming out in the last 2 – 3 years a lot by Dr Kline in the US – and some new guidelines have been produced based on the studies.

The basic strategy here is to try and stratify the patient with PE into groups – kind of how we do with ACS, the different risk groups get a different management plan.

So how do we do this? There are a few criteria:

- Blood pressure / shock – patients with low BP (less than 90 systolic for >15 minutes) are called MASSIVE PE

- Those with no shock but evidence of cardiac strain eg. troponin, BNP rise, a dilated RV / increased RVP are called SUBMASSIVE PE

- Then the others – the ones with normal cardiac markers, normal haemodynamics etc are the NOT MASSIVE PE.

Makes sense? It is a bit of odd nomenclature but that is what we call em!

The real controversy here is deciding whom to use thrombolytics upon in the SUBMASSIVE group, and who just gets heparin and watching – traditional management for most of us.

So lets go back to our case. The CTPA is convincing – he has a big PE(s). But what about his other markers of severity?

And using a super-sensitive troponin we got a small bump of 0.19. So he has 2 factors that suggest his heart is struggling.

I asked Scott Weingart this question and he answered it on his recent Emcrit Live #2 show – Scott reckons he would take the lytics, but the evidence suggests the benefit is about improved function / exercise tolerance later – not so much about improved mortality in the short term. the risk of a bad bleed is small – 0.5 – 0.9% depending on what you read.

The AHA published its guidelines in Circulation , March 2011. Follow this link to a nice algorithm that I think is reasonably practical and allows us to make an informed decision with the patient about risk.

There is certainly enough wiggle room in the data to mean you should discuss the pros and cons on a case by case basis. remember you are not likely saving a life – just making the long term function better, so your baseline level of function comes into this discussion I think.

So here is my question – would you offer thrombolysis to this man in your hospital? Let me know on the comments…

Further food for thought – this retrospective analysis of “unstable PE’ patients in American Medical Journ. May 2012 appears to show all cause mortality was improved with thrombolytics in the sick end of the disease.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

hey casey,

im going to sit on the fence on this one.

personally would be leaning towards tpa.

discussed case with the three in house physicians.

got a 2:1 split in favour of not giving tpa.

reasons for this were simply I dont see enough and

wouldnt be comfortable doing for unclear gain. other

boss who was keen to felt “hes just young and buggered

lungs is a terrible thing”

so I guess thats bit more mud in the water.

cheers.

keeweedoc

Thanks for the case, Casey! I have been following the discussion with you and Scott and others about this issue of thrombolysis in submassive PE. Here is my two cents and some cautionary tales

In my opinion , if you have imaged thrombus in a pulmonary vessel AND have signs of objective cardiac dysfunction/injury AND have a good story for acute onset ( <6hrs), then I would recommend giving lytics to that patient.

To me it is analagous to STEMI.

Now cautionary tales. What about pregnant women presenting with syncope, hypotension and tachycardia? Be very careful in your workup. I have reviewed two cases where the PE suspiscion led folks down the line of starting heparin and in one case, giving lytics for supposed right ventricular dysfunction on bed side echo. Case that got heparin, in fact was a ruptured ectopic and luckily survived after a FAST scan revealed pelvic free fluid. Case that got lytics, died from undiagnosed uterine rupture. No PE on autopsy. Amniotic fluid embolism in pregnancy can present as PE picture! Now that raises the issue, how do you PE workup a pregnant woman..CTPA, VQ, MRA ? And would you give lytics to a pregnant woman with submassive PE?

No one where I work seems to want to thrombolyse sub-massive PE’s. We’ve had 2 cases in the last 12 months with signs of RV dysfunction and persisting lower limb DVT. Both got sent to interventional radiology for a caval filter.

Whilst I’m reluctant to disagree with Minh on anything because a) he’s smarter than me and b) I’m pretty sure he some sort of Wing Chun grandmaster who could beat the crap out of me using the little finger of his non-dominant hand, Jeff Kleine at Essentials last year made the point that when it comes to thrombolysis, a PE is not like an AMI. He argued you can wait several days before giving thrombolysis and still get improved functional outcomes.

Casey,

thanks for sharing this case.

To thrombolyse a sub-massive PE is a therapy not easy to accept for physicians and patients too. Not immediate advantages and some, not negligible risk.

In my experience most of us are reluctant to take that risk.

The AHA algorhythm could be a path to follow but the best answer to your question is in your post already:…you should discuss the pros and cons on a case by case basis. remember you are not likely saving a life – just making the long term function better…

thanks guys for your candour. indeed PE is not like CAD or ACS . you cant intervene with secondary prevention strategies like lipid lowering or antiplatelet therapy. you either get life long anticoagulation if it recurs or a caval filter…or both.

you cant do PCI or CABG like you can for STEMI or NSTEMI

BUT thrombolysis is licensed for both STEMI and PE. STEMI and submassive PE both raise cardiac injury markers which is associatd with worse morbidity and mortality

The best current evidence suggests a trend towards mortality benefit albeit not stat significant due to small trial numbers and wide confidence intervals

There is sufficient biologic plausability and evidence for me to recommend to a patient with submassive PE that they will do better with thrombolysis. I would recommend this to a loved one. Scott would to from the sounds of things on his recent podcast.

The comparison of PE thrombolysis to STEMI is not really a good one. The analogy from the kitchen would be putting butter in a hot pan (STEMI) vs. using a hairdryer to defrost your freezer (PE) over a few hours.

The ED perspective is a bit warped as the patients don’t look better in ED time scales, it is the longer term chest function that you see months later that one needs to look at for a real benefit.

The evidence is there – both Jeff Kline and Scott Weingart have stated they would go for the lytics if it were their heart / lung. But don’t expect the patient to look great in the next few hours.

thanks CAsey! Now what about pregnant women, mate? what would you do for them in Broome with suspected submassive PE? run through the CT or fly them out for MRA, VQ?

If hypoxic and positive BNP, troponin, would you lyse without CTPA, or for that matter, if you had a positive CTPA

Ah, MInh. You are killing me!

I think the safest option for a pregnant woman with a good story / work-up suggesting PE would be to fly her out on a heparin infusion to a big centre where she could have an MRA or CT / VQ depending on the centre. I would not thrombolyse her in Broome as the risks are increased and it can wait until tomorrow.

The last thing I want to do is create a crash C-section, on a bleeding woman with a 29 week fetus… I just don’t have enough hands to cope with that many resuses at once!

Would be a very long day for all concerned!

On the risk of CTPA in pregnancy – depends on gestation, if very low risk – maybe not, if very high / sure on other clinical features (eg. big DVT plus chest signs) then heparin without a CT?

It is the middle that is tricky – fly em out with heparin on board would be my bet.

C