Clinical Case 147: Going Slow Nowhere Fast

It has been 2 and a half years since I wrote the last Broomedocs Clinical Case, #146 … and I have recently had a few random readers ask me… “can you write more cases?” So I thought it was a good idea to get back to some cases, after all it is what we do! So here we go, another very Kimberley case for you to wrap your neurons around.

On a quite Sunday morning in the middle of the wet season the BAT phone rings… The ambos are bringing in a 57 year old man who has collapsed at home. The ambos have recorded his pulse at 27 /min and a BP of 60/40, he is pale and in and out of consciousness. They have given a dose of atropine and 500 mL of saline with no effect. In the five minutes that it takes the ambulance to travel across town a quick check of the Bureau of Meteorology website reveals that a tropical cyclone has crossed the border in the east Kimberley and is tracking towards Broome… it will be getting wet and wild in the next 24 hours.

On arrival to the ED I recognise the patient immediately, Jimmy. I gave Jimmy an anaesthetic just a few months ago. To be more accurate I performed a supraclavicular block for the formation of a new AV fistula… Jimmy has end-stage renal disease and is planning to start dialysis once it is required. Typically we like to let an AV fistula graft mature for 3 months before using it. Jimmy’s graft is looking good, the scar has healed nicely and a quick palpation reveals a healthy thrum of flow. One of the perks of being a small town doc is that the patients are often very familiar, it makes for easy history and care!

His wife says that he has been well aside from a small toe infection in recent days. As the nurses attach the monitors it is pretty obvious what is going on… end-stage renal disease and severe bradycardia… its gotta be the potassium!

Here is the initial ECG:

normal QRS peaked T-waves lateral leads…. this is all consistent with hyperkalemia

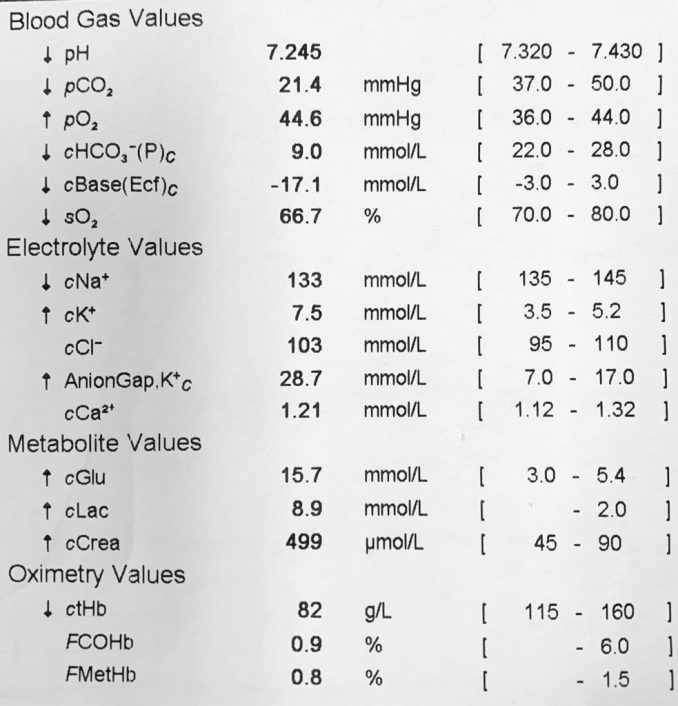

So now, we can run a quick VBG in the ED but it is a Sunday so – no formal bloods will be available. Here is the VBG result:

So action stations. We need to get that potassium back into the cells and stabilise the myocarduim before Jimmy’s heart stops altogether.

- Calcium – gluconate bolus to stabilise the myocardium and get that action potential closer to where it should be.

- Fluids… this is a bit tricky. He is in advanced renal failure and may not be able to deal with too much volume… but his BP is super low. Maybe some volume will allow his failing kidneys to excrete some of that potassium. So which fluid will you give? Saline is easy to hand… but that chlorine may push our acidosis in the wrong direction? So what about a balanced solution? Well they all have potassium in them, which is not as big a problem as it may seem… but there is a better option here: isotonic bicarb

-

- Grab a bag of 5% dextrose, suck out 150 mL, then add 150 ml of NaHCO3 8.4%, viola. You have a balanced fluid with no potassium and will bring the pH up towards normal.

-

- Insulin – Jimmy has plenty of glucose on board and we are running in more. – so insulin can be dosed liberally. Traditionally we have given 10 units of short-acting insulin… but recent studies [La Rue et al] suggest that giving 5 units is as good as 10 … and we can also give another dose after a while if we need.

- Salbutamol is another option we can use to drive some potassium into the cells. The main side effect of salbutamol is tachycardia… which is kind of useful in Jimmy’s case. So there is not much downside here, so using a nebule or two can help bring the K down 0.5 – 1 mmol as a bonus.

Now after all of that we have repeated the VBG and the potassium has come down to 6.0 and the heart rate is up to 50/min and the p-waves have returned… Jimmy is feeling much better and pink and his perfusion returns… that is all we need to do right? Well, no! Thus far we have merely shifted the potassium around but it is not going to last. We need to eliminate some potassium from Jimmy’s body. So how are we going to do this?

Potassium elimination can be done by number 1 or number 2s! Increase the renal excretion or though the alimentary canal – usually using a combination of resonium resin and laxatives.

We can start with the number 2s: this is not really an option here – alimentary excretion is slow and unreliable. Resonium (Kayexelate…) really has very little evidence to support it s use in acute settings. There is also significant concerns about the safety of Resonium, which has been associated with ischemic bowel… however there is a new player in this space – Sodium Zirconium Cyclosilicate. [SZC]. SZC appears to be safe, but slow. The studies show it may drop the K+ by 0.4 mmol per day… and that may come in handy tomorrow… but not today.. and this medication is not really available in many small hospitals. So we can not rely upon number the alimentary potassium passage.

So now we need to consider the renal route. Jimmy has end-stage failure of the kidneys. He reports that he does still produce small quantities of urine and he is prescribed 250 mg of frusemide a day. A quick review of Jimmy’s recent bloods show that his creatinine clearance has been quite stable in recent months since his fistula creation. His creatinine and urea on todays bloods are essentially the same as they were a month ago… Hmmm. What is going on here. Why has his potassium suddenly jumped up to threaten his heart? Does he have BRASH syndrome? This is a relatively recently described dynamic process that can occur in patients like Jimmy which can quickly spiral into disaster.

However, Jimmy seems to be quite well recently, he is not on any AV nodal blocking drugs. He has had that toe infection, but was never septic. His GP has been treating the small erythematous skin area with a 5 day course of Bactrim (co-trimoxazole).

So BRASH syndrome is not likely… we have 2 options to remove potassium from his system. Either via diuresis or dialysis.

This is where the logistics of remote practice become tricky. We can give Jimmy volume and diuretics and hope his failing kidneys can excrete the excess K+. That but is easy… but acute dialysis is tricky.

Our hospital, like most small places does not offer acute dialysis, nor does it have capacity to dialyse acutely unwell patients. Jimmy is certainly too unwell to go to outpatient dialysis. He has a fistula which may be ready to use… but the initiation of dialysis is usually done in a tertiary Renal centre until the patient’s filtration goals are established…

So despite having access and being near a dialysis machine – we cannot dialyse Jimmy. So the plan is to get Jimmy to a big hospital where he can get dialysis if he needs it… onto the phone.

The Renal Physician in the big hospital 2000km away turns out to be an old mentor, a gentleman of medicine. You describe the situation and suggest that we fly Jimmy south now to start dialysis. But… there is always a but… the Renal doc has a hunch that Jimmy is not needing dialysis just yet. True, his numbers seem to be unchanged. He is still making a bit of urine… so can we keep him in Broome? Wait a while and see how he goes?

AS you are on the phone weighing the pros and cons the Nurse manager slips a copy of the latest cyclone report under your nose:

The decision is now in the hands of the weather Gods… There is about a 1-hour window where a retrieval flight will be able to take off.. after that there will be no flights for days…

At this point the friendly Renal doctor asks… why is the potassium suddnely so high. Jimmy’s numbers just do not make sense – something is up…

Can you work out why Jimmy is suddenly sick and bradycardic with a super high K+??

Would you jump on the phone and book a flight out ASAP to get him outta Broome… or play it cool and keep him for what may be a week without access to dialysis?

Trimethorprim has a very similar structure and mechanism of action as amiloride – a potassium-sparing diuretic that acts on the distal convoluted tubule. The effect is particularly present in patients with chronic renal disease and those on ACE / ARBs … and worse in end-stage renal disease where the threshold for adequate potassium clearance is just being met.

So be careful when prescribing common medicines to patients with renal disease – there are a number of antibiotic s and other agents that are potentially dangerous in these folk – always check before you treat.

Brilliant Case described in the real world of remote medicine.

Thanks for taking the time and energy to write, Casey.

I would probably keep him in the circumstances–storm coming in puts Jimmy in the lap of the gods, as you say. I’m guessing that’s what you did.

The observation about Trimethoprim makes for a twist in the ending for those of us (like me) who didn’t know that. We are coming across Trimethoprim resistant UTIs in Central Australia in the past few years. Now, I have another reason to be cautious with it.

Appreciate the teaching in a story, always the best way to learn.